Steelmanning in the act of taking a view, opinion, idea or argument and constructing the most generous, charitable and strongest possible version of it. This is best done on beliefs you strongly disagree with to find out if you have rational reasons for your disagreement. It works even better if you try to steelman different sub-opinions on the same topic and decide which steelman best applies. In many cases you will find yourself combining and integrating the strongest points from each steelman into your own version of the topic, creating the Optimus Prime opinion on any given topic.

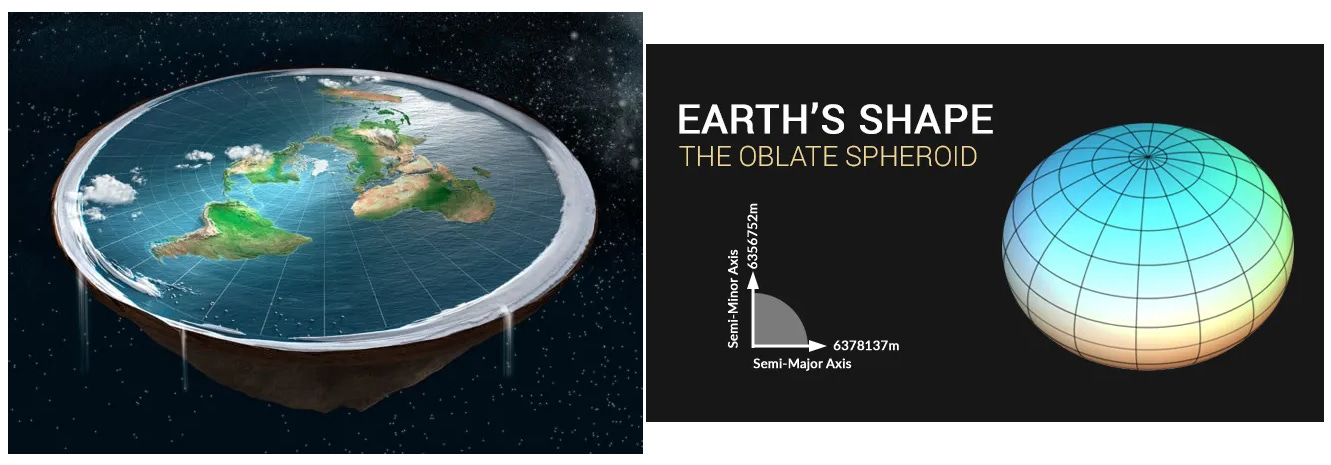

Let’s take an example. If you believe the Earth is a sphere then try to steelman why the Earth is flat. And you will find some very interesting scientific sounding arguments for the spinning disc hypothesis. You could even join The Flat Earth Society and go check out their library, forums, podcast or conferences. After you come out of that rabbit hole then try to come up with the best explanation for why the Earth is a sphere. Eventually what you will find is that the Earth is neither a perfect sphere nor flat. The Earth is actually an oblate spheroid. It’s stretched out along the celestial equator because it’s spinning so fast.

Steelmanning is part of the tradition in the debates of Indian logicians and is called Purva Paksha. My dad is constantly trying to remind me of all the great Indian CEOs and politicians and now I finally can enlighten him of something even more inspiring to come from Indian culture.

Steelmanning is also one of the central wisdoms of American billionaire investor Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway. Called “Munger’s Iron Prescription”, it cautions the mind to be weary of the dangers in submitting to a particular ideology. At his celebrated commencement address to the graduates of the University of Southern California Law School on May 13, 2007, Munger affirmed:

I have what I call an “iron prescription” that helps me keep sane when I naturally drift toward preferring one ideology over another. And that is I say, “I’m not entitled to have an opinion on this subject unless I can state the arguments against my position better than the people do who are supporting it.” I think only when I reach that stage am I qualified to speak.

…

This business of not drifting into extreme ideology is a very very important thing in life if you want to have more correct knowledge and be wiser than other people. A heavy ideology is very likely to do you in.

The opposite of steelmanning is called strawmanning. A strawman is when you distort an idea in order to make it easier to attack or dismiss. Essentially, the person using the strawman pretends to attack an idea they already disagree with, while in reality they are actually attacking a distorted version of that idea, which their opponent doesn’t necessarily support.

For example, if someone says “Because of the thefts in our building, I think we should add more security cameras.”, a person using a strawman might reply with “So you’re saying you don’t trust your neighbors?”. A strawman is a form of argument that is considered a fallacy in thinking and debating.

While the skill of steelmanning is not that hard to do, the underlying discomfort of being wrong and being humbled by it definitely is. The urge to correct another from a wrong assertion is also hard to suppress. This urge is so common that a counter-intuitive way to find the correct answer on the internet is to post a wrong answer, known as Cunningham’s Law. I struggle with these tendencies consistently especially in conversations with those who I disagree most. I’ve been on the business end of cancel culture a number of times over the last few years and I attribute that mainly due to not demonstrating the art of listening curiously and steelmanning perspectives before offering any criticism. The best antidote I know for these tendencies is a list of rules promulgated many years ago by social psychologist and game theorist Anatol Rapoport:

You should attempt to re-express your target’s position so clearly, vividly, and fairly that your target says, “Thanks, I wish I’d thought of putting it that way.”

You should list any points of agreement (especially if they are not matters of general or widespread agreement).

You should mention anything you have learned from your target.

Only then are you permitted to say so much as a word of rebuttal or criticism.

Your conversation partners will immediately be a much more receptive audience to your opinions, ideas and criticisms.

Such a strategy can also help sift through who the real experts vs. the faux ones are on any given topic regardless of their credentials. These days you can find a PhD on any topic that supports a particular view. Known as Gibson’s Law that “For every PhD there is an equal and opposite PhD”. Having a PhD doesn’t put someone closer to the truth, it often just makes them more adept at arguing for their side. The best way to sift through such “experts” is to ask them what experts on the other side of the debate would say on a given topic. Those who can steelman the opposing perspective is likely the expert.

We are constantly bombarded by a culture that demands we know all the facts, win an argument, get the correct answer, be right. In school we have speeches, tests, sports, games and debates that all demand we win the contest. On TV, there’s jeopardy and the myriad of trivia shows that want us to know all the facts. On social media, being wrong can put you on the dogpile end of a viral video. And so many of us adopt an identity of the debate team captain who’s self worth is defined by our ability to use facts and rhetorical tricks, like strawmanning, to win our side of the argument. Our entire concept of intelligence and being smart is defined by how right we are. So we seek out reasoning, evidence and data to confirm our righteousness. I advocate for the exact opposite. Try to be more wrong. Try to disconfirm your beliefs. But admitting to being wrong hurts us and we do everything in our power to avoid it. We become a slave to our egos rather than a seeker of truth.

Steelmanning flips this paradigm on its head. Truth, curiosity and humility become more important than knowing everything, being right and winning an argument. You may be wrong more often and you’ll rarely get the satisfaction of winning an argument. But over time you’ll skyrocket your learning, be much less wrong and perhaps learn to have better conversations with those who disagree with you. Those are victories worth having.

“He who knows only of his own side of the case, knows little of that.”

-John Stuart Mill, On Liberty